-Edit: this blog entry was written well before Marvel started muddling about with time travel, and even though I do actually nail some points made by one of the characters in “Avengers, Endgame”, it was never intentionally meant to provide spoilers for that or any subsequent Marvel movie.

That said, if you’ve seen the film and want to dig into the details of the rules of time travel, read on, there will be no intentional references or spoilers regarding “Endgame” or other MCU stuff, although it might be fun to see if I score any other unintended quotes. –

So you wish to include time traveling as part of your story? How hard can it be? Have a nutty scientist or brainy professor come up with a credible time machine, or stumble across one if you want to avoid some of the techy mumbo-jumbo, have them jump backwards or forwards to the time requested by the plot, and then, for the perfect Hollywood ending, everyone jumps back to their timeline and enjoys the cool effects of tweaking history.

Problems deriving from time-travel? There’s nothing so terrible about becoming your own father or mother (or both) that can’t be fixed with some counseling and some good parenting. (I think Douglas Adams said that.) It’s just like wiping a page from a history book and writing it again the way you want it to be, right?

Wrong.

The truth is that when it comes to time travel, the territory becomes rather uncertain if not entirely boggled. Here are ten things you should keep in mind when you start playing around with time.

1. If you are about to leap into the past, then it has already happened.

That’s right. The moment you allow your characters to jump back in time, then the alterations they will apply will already have taken place. This results in our first great dilemma: now that history has changed and the problem solved, what will motivate the heroes to jump back? When the solution is so effective that the problem never existed, who will need to think of a solution? One way to solve this is to conceal the fact that the current state of affairs is, in hindsight, a result of that jump, and that another, far worse, scenario would have ensued from not going back. In other words, the travelers’ motivations are not determined by something that will change, but something they have already changed.

2. Your traveler must, in no way, be connected to the facts he or she is trying to change.

As a collateral point to rule number one, any traveler altering events impacting their own timeline will automatically fail. This is because, by altering time, they will inevitably alter their own memory of what happened, and that will ultimately lead to different decisions the next time around.

“Wait what next time?”, you ask. Well that leads us to:

4. It’s a loop. An infinite one.

Get it?

3. It’s a loop. An infinite one.

A successful leap into the past is one that will always have happened. One in which the traveler will, at a certain point, either devise their own way to travel, or be thrown back in time by a series of events which must, always, result in the same outcome. Time will not permit an ever-changing number of different outcomes, it will stabilize into a flow where the jump never happens, or where it does, but always follows the same exact script. The effects of this on the characters can be very dark, or also quite funny. Especially for short jumps. Just like this little joke.

5. Time is memory.

In other words, our only sense for the passing of time is our ability to keep a record of past events. As a result, altering time inevitably alters the record. There are only two ways out of this paradox, in my opinion: One way is based on the theory of alternative universes which is so popular nowadays. In this theory, when you travel in time what you really do is jump to a different reality where what you did has changed history, but you come from a universe where nothing was done, so your memory of that history remained the same. This theory has a few flaws, well pointed out by the Rick & Morty series, including meeting infinite yous intent on changing their histories, and infinite other yous content with their lot and suddenly buggered by all the goddamn people turning up at their door.

Another way is to have time change from the old reality to the new rewritten one, but slowly. Slowly enough for the transition itself to be noticed and recorded. This is what I did in my short story “Hero of Stolen Time”. In it, the hero Ratscrap is the only one capable of jumping back two years into the past to stop the beginning of a terrible series of Viking incursions. When he fails to do so, partially because Ratscrap is a self-loathing coward, reality slowly begins to shift to a Viking-ridden village where everyone’s soon-to-be alternative is killed. Knowing this, Ratscrap must jump back to preserve his reality as well as his own miserable life.

6. The Bootstrap Paradox.

This theory was described quite beautifully in a Dr. Who episode and went like this:

Imagine your character is a Beethoven fanatic. He packs his collection of sheet music and jumps back to meet the man himself to discuss all things musical. When he finally sees Ludwig, our hero is horrified to discover the great composer doing nothing but sitting on the sofa and scratching his butt. (I think the Doctor put it more elegantly). Panicking, the time traveler shoves all of Beethoven’s sheet music in the loafing musician’s hands and hurriedly leaps back to the present to discover, to his relief, that the great Ludwig still is the world-renown musical genius.

The paradox is this: who composed the music? Our hero would swear it was Beethoven, but Ludwig would say it was a frantic looking man with a funny German accent who made it and gave it to him. You can’t jump back in time and hand J.K. Rowling a copy of Harry Potter. That’s worse than becoming your own parent.

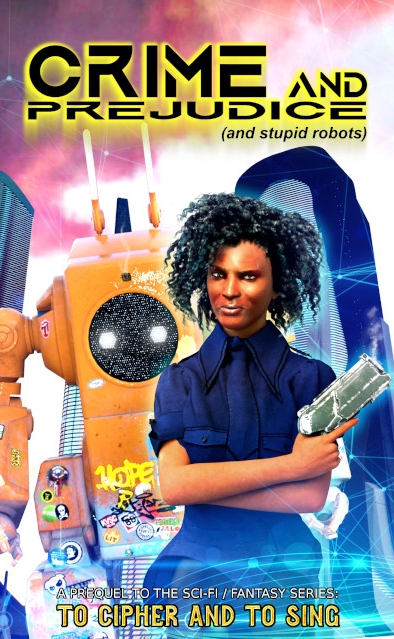

“The Fairlight Project” book series is based on a 500-year long bootstrap paradox.

.

7. I don’t have time for number 7.

Grab a free ebook,quick & fun to read, here.

8. Beware the uncanny valley. (Yes, there’s one in time travel too)

People who read sci-fi appreciate the imaginative way authors apply their scientific knowledge. A lack of scientific detail will undermine the credibility of your story. When it comes to time and time travel, science itself becomes rather iffy. To put it in other words, there’s a whole lot of fi in the sci already. Some writers will try to compensate this by adding even more details on exploiting naturally occurring nano-wormholes, strings, membranes and that ever recurring buzzword, the quantum [insert something here]. The result being that, past a certain threshold, the authors themselves get so garbled as to put off even the most hardened geek. Make it scientzy, but don’t overdo it. Sometimes it’s preferable to simplify too much rather than overexplain it. Ratscrap’s time jumping ability, for instance, came from a simple magic potion.

A magic potion? Jeez, who am I trying to fool here. That’s almost as bad as quantum.

9. Forward jumps are ok. Sometimes.

Making your hero jump forward in time is absolutely doable. Unless you have the nerve to also bring them back. In that case all of the above rules apply again. Knowledge of future events could potentially lead to attempts aimed at altering that future, but in that case, the original future never existed, so why change it? Head aches anyone? (One of Ratscrap’s side effects of time travel was a massive, sentient head ache).

10. Alternatives to time travel.

There are a couple of more approachable alternatives to time travel, to avoid headaches, embarrassing family reunions and all that excessive mucking about with quantum and J.K.Rowling.

One way to travel into the past safely is to “tune in” to a past moment. This can be done by sending back a hidden probe, or waiting for when everyone will have a memory chip installed into their brains and simply play back their experience, or even sync present and past atoms to create a replica via, sigh, quantum entanglement. In all three cases the past cannot be altered but only experienced as a hologram or virtual reality.

Another alternative to changing the past is even simpler. As stated in rule no. 5, time is memory. Do you really need to send your character back in time to hide the fact that they murdered someone? Wouldn’t it be relatively easier to alter everyone’s memory of the event, so that the murder becomes an accident? In this case the hero’s memory would remain intact, as well as anyone’s they wish to preserve.

Thank you for reading my ten rules of time travel. These are just ideas, not to be taken as absolute guidelines. Just make sure your plot holds, maybe catch a glimpse of the future to check how readers will respond and you will have seen – are going to have seen…

Truth be told, hardest thing about writing time travel are the damn tenses.

Ian Lahey writes humorous science fiction and fantasy. He spends the days reminiscing the time when a book critic used his name alongside those of Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett. The critic also used “nowhere near” and “what a pillock” but these are trivial details. You can judge for yourself by grabbing one of Ian’s books or, if you’re inclined for a short read or just not ready to cough up real money just yet, pick up a free short story here.

It’s already happening.

Is it time to succumb to our AI overlords? Relax. We already have.

Be my Valent(AI)ne

We asked our resident AI to compose some verses for Valentine’s day. Here are your AI Valentine cards, straight from Adam.

Could she be real?

Part of my ongoing experiments with AI and AI-powered filters, the task was to render the face of a beautiful woman who is, in reality, a robot. This artwork has been minted as NFT. You

Queen Mab

Still exploring the amazing ability of AI when it comes to generating images starting from simple words, such as “Queen Mab on the Golden Throne”. Clicking on the image will take you to the NFT

Hits: 23159

Do you have a free giveaway of aspirin for readers? My poor brain was battered by the conundrums of time travel—and then you hit me with Dogecoin? More than I can wrap my thoughts around.

Great article. It convinced me to keep my sci fi writing linear along the time-axis.

I really wanna travel to the 18-century.